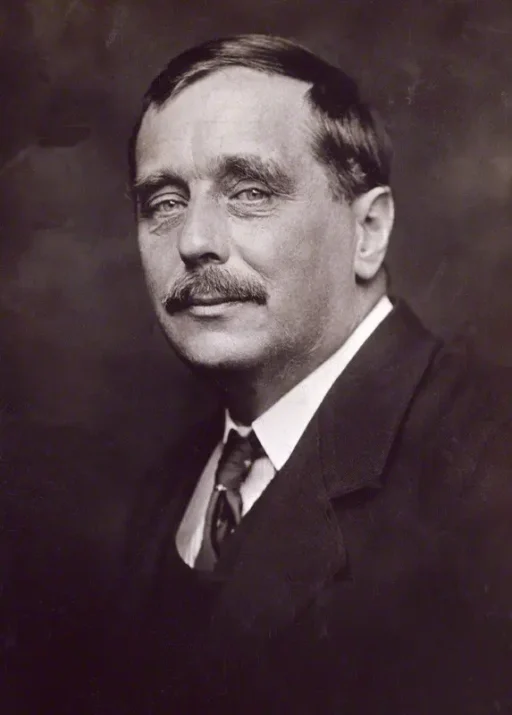

Herbert George Wells (1866–1946)

The Architect of Science Fiction

H.G. Wells is one of the founding giants of modern science fiction. His works introduced many of the key tropes—time travel, alien invasion, invisibility, dystopian futures—that remain central to the genre today. Wells used storytelling not just to entertain but to critique society and explore humanity’s possible futures.

Biography in Brief

- Born: September 21, 1866 — Bromley, Kent, England

- Died: August 13, 1946 — London, England

- Nationality: English

Born in Bromley, England, in 1866, Wells came from humble beginnings. Despite financial struggles and frail health in his youth, his intellectual curiosity drove him to rise above his modest roots. He left an early apprenticeship as a draper to pursue science, studying biology under T.H. Huxley (aka “Darwin’s Bulldog”). This scientific training deeply shaped his Darwinian worldview, which became central to his writing.

In the 1890s, Wells began publishing what were then called “scientific romances.” These novels combined emerging scientific theories with speculative leaps, imagining consequences for humanity. Over his career, he wrote around 50 novels, 80–90 short stories, numerous nonfiction works (including histories and political treatises), and various plays, poems, and essays.

About twenty novels and many short stories were science fiction, but most of his work spanned other genres. He wrote social comedies and realist novels, imagined utopias and dystopias, and produced sweeping works of history and political commentary. His range made him as influential a public intellectual as he was a storyteller.

Wells lived through immense social change, including two world wars. His writings often carried warnings about technology, oppression, and unchecked ambition. He remained an influential public voice until his death in 1946, and his works have continued to shape science fiction and social thought ever since.

Key Sci-Fi Works

- The Time Machine (1895)

Introduced the idea of time travel by machine, exploring class struggle and humanity’s far future. - The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896)

A disturbing tale of vivisection and the blurred line between man and beast. - The Invisible Man (1897)

A story of scientific obsession, power, and alienation, centered on a man rendered invisible. - The War of the Worlds (1898)

The classic alien invasion story, using Martians as a mirror for British imperialism and human fragility. - The First Men in the Moon (1901)

A lunar voyage that explores an alien civilization as a mirror to humanity’s own social and political structures.

Contribution to Science Fiction

Wells was the architect of science fiction’s modern form. His science-based stories probed “what if?” questions and their human consequences. Instead of relying on the supernatural, he built his tales on believable extensions of real science—evolution, astronomy, physics, chemistry.

While Jules Verne used the science of his day to craft thrilling adventures of exploration and discovery, Wells took the same starting point in a different direction. For him, science was a tool to ask hard questions, turning new ideas into social critique and cautionary tales about humanity’s future.

He also created lasting icons: time machines, hostile aliens, invisible men, and dystopian futures. Mary Shelley had already shown that science fiction could warn about reckless creation (Frankenstein) and picture the end of humanity (The Last Man). Wells expanded those foundations, giving science fiction the framework of speculative scenarios that still shape the genre today.

Legacy & Influence

Wells’ fiction has been adapted into countless forms of popular culture. The War of the Worlds alone has sparked everything from the infamous 1938 Orson Welles radio broadcast to Jeff Wayne’s hit musical, Spielberg’s 2005 blockbuster, and even the recent (if poorly received) Ice Cube screenlife adaptation. Each new version—whether faithful or loose—demonstrates how deeply Wells’ vision continues to resonate.

His imagination also proved remarkably accurate. Decades before their invention, he described atomic bombs, tanks, aerial combat, genetic engineering, and worldwide information networks. For this, many have called him not just a novelist but a futurist whose ideas helped shape the very course of technological progress.

Wells’ influence on later writers is immeasurable. George Orwell and Aldous Huxley carried forward his dystopian concerns. Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov developed his vision of science as a driver of both wonder and warning. Ursula K. Le Guin, Ray Bradbury, and countless others found in Wells a model for blending speculative ideas with human insight.

Beyond literature, Wells’ ideas reached into science and politics. His calls for global cooperation and education inspired figures ranging from statesmen to working scientists. Even today, his works continue to challenge readers and viewers to think critically about technology, morality, and the future of humanity.

Related Blog Posts

👉 Explore related posts about H.G. Wells:

🎤 Sci-Fi fight fans, welcome to tonight’s main event! In the red corner, hailing from Bromley, England… he brought us time travel, invisible men, and Martian war machines… the sharp-eyed pessimist who built frameworks of progress, catastrophe, and consequence… it’s H.G. “The Architect” Wells! And in the blue corner, from Nantes, France… he sent submarines

Sources & Further Reading

- H.G. Wells, The Time Machine (1895)

- H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds (1898)

- H.G. Wells, The Invisible Man (1897)

- H.G. Wells, The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896)

- H.G. Wells, The First Men in the Moon (1901)

- H.G. Wells Biography at War of the Worlds Central: An overview of his life, works, and cultural legacy, with focus on the creation and lasting impact of The War of the Worlds.

- Huntington, John. The Logic of Fantasy: H.G. Wells and the Problem of Utopia. Columbia University Press, 1982. This scholarly work examines the utopian and dystopian themes in Wells’s science fiction, offering a sophisticated look at his social commentary.

- Parrinder, Patrick. H.G. Wells: The Critical Heritage. Routledge, 1972. This is an essential resource that collects contemporary reviews and critical essays on Wells’s work, providing insight into how his “scientific romances” were received at the time of their publication.

- Project Gutenberg: For direct access to his works. Since most of his works are in the public domain, this is an excellent, free resource for readers.

- Sherborne, Michael. H.G. Wells: Another Kind of Life. Peter Owen Publishers, 2010. This more recent biography offers a nuanced, modern perspective on Wells, focusing on his private life and personal relationships, and complements the more public-focused biography by Smith.

- Smith, David C. H.G. Wells: Desperately Mortal. University of New England, 1986. This is a respected scholarly biography of Wells, which is especially strong on his public life as a “utopiographer” and social reformer, providing excellent context for the “architect” role.

- The H.G. Wells Society: The official website is a great resource, offering a wealth of information including a detailed bibliography, academic papers, and news about Wells-related events.

- The Victorian Web: This website offers a collection of scholarly essays and contextual information about the Victorian era, including sections on science, technology, and literature, which are crucial for understanding the influences on Wells’s work.

- Wagar, W. Warren. H.G. Wells: Traversing the Time Machine. University Press of New England, 2004. This book provides a detailed analysis of The Time Machine and places it within the context of Wells’s life and intellectual development.

Frequently Asked Questions

A: Wells wrote groundbreaking “scientific romances” that shaped the modern genre — exploring time travel, alien invasion, and invisibility with a mix of science and social critique.

A: The Time Machine (1895), The War of the Worlds (1898), The Invisible Man (1897), and The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) are classics still widely read today.

A: No, earlier stories like Edward Page Mitchell’s The Clock That Went Backward (1881) and Enrique Gaspar’s El Anacronópete (1887) used mechanical time travel. However, Wells’ The Time Machine (1895) popularized the idea of a controllable, vehicle-like machine for navigating time, creating the enduring trope central to modern science fiction.

A: No — he also wrote social commentary, history, political essays, and utopian/dystopian works. He was as much a thinker and reformer as a storyteller.

A: He saw history as a race between education and catastrophe — a theme that runs through much of his work.

Affiliate Disclosure: Some links on this page are affiliate links. If you click through and make a purchase, Founders of Sci-Fi may earn a small commission—at no extra cost to you. Thanks for supporting the site!