Mary Shelley (1797–1851)

The Grandmother of Science Fiction

Mary Shelley is widely recognized as the pivotal figure who helped shape speculative tales into a modern genre. While earlier writers imagined fantastical voyages, Shelley grounded her premise in the scientific debates of her day, creating a new kind of storytelling.

At just 18, she began Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818)—a groundbreaking novel that fused Gothic horror with current science and asked enduring questions about creation, responsibility, and the limits of human ambition. The novel helped establish foundational tropes of science fiction.

Biography in Brief

- Born: August 30, 1797 — London, England

- Died: February 1, 1851 — London, England

- Nationality: English

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was the daughter of political philosopher William Godwin and feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft. Growing up surrounded by radical thinkers, Mary Shelley absorbed the rational ideals of the Enlightenment alongside the emotional fervor of Romanticism.

Her pivotal moment came in 1816, during a fateful summer at Lake Geneva with Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Polidori. A ghost-story challenge led her to conceive Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Published in 1818, it launched her literary career and helped define a new genre.

Shelley went on to write further speculative works, including The Last Man (1826), one of the earliest apocalyptic novels, while also editing and preserving Percy Shelley’s writings after his death.

Key Sci-Fi Works

- Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818; rev. 1831)

A cautionary tale of unchecked scientific ambition—often cited as the first true science-fiction novel.- The subtitle recalls the Greek myth of Prometheus, who gifted fire to humanity and was punished—mirroring Victor Frankenstein’s hubris and suffering.

- The 1831 revision reframes parts of the origin and themes; it takes on a more fatalistic tone, suggesting Victor’s path was guided by destiny rather than free will.

- The Last Man (1826)

An early apocalyptic vision of plague wiping out humanity.- Often regarded as the ancestor of modern post-apocalyptic fiction, it blends Shelley’s personal grief over lost loved ones with a speculative vision of civilization’s fate.

- Short stories with speculative themes, including “The Mortal Immortal” (1833); “Transformation” (1831); and others.

Contribution to Science Fiction

Mary Shelley helped invent the scientific cautionary tale: what happens when human ambition collides with emerging knowledge. Unlike Gothic predecessors who relied on the supernatural, Frankenstein is rooted in live debates about galvanism, anatomy, chemistry, and vitalism—theories some contemporaries believed could unlock the principle of life.

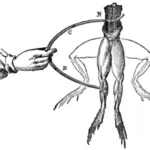

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Luigi Galvani’s experiments—electric currents causing muscle contractions in dissected animals—sparked public fascination with electricity as a possible ‘life force.’ Shelley channels that aura of possibility and dread, then pushes it further: she makes the ethics of creation, accountability, and social consequence the heart of the story.

Her template—technology plus responsibility—echoes through H.G. Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau, and onward to modern debates about AI, cloning, and biotechnology.

For a deeper look at how Frankenstein became the birth of modern science fiction, see our full blog post on the novel’s groundbreaking role.

Legacy & Influence

Shelley’s impact extends far beyond literature. Frankenstein has become a modern myth, adapted for stage, screen, and every corner of popular culture. Its “mad scientist and monster” archetype still shapes science fiction and horror today.

Her second major speculative novel, The Last Man, helped establish the enduring appeal of apocalyptic science fiction. Its vision of plague and societal collapse echoes forward into later science fiction, from Matheson’s I Am Legend to Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy.

Mary Shelley is rightly remembered not only as a key founder of science fiction, but as the architect of keystone questions that still shape the genre. In an age of AI and genetic engineering, her questions feel newly urgent: What responsibilities come with creation? Where are the limits? What happens when we push too far?

Related Blog Posts

👉 Explore related posts about Mary Shelley:

Mary Shelley didn’t invent Frankenstein out of thin air. When she began writing her novel in 1816, science was pushing the boundaries of life, death, and electricity — and she was paying close attention. Her tale of Victor Frankenstein, a science student obsessed with reanimating the dead, grew directly out of the discoveries and debates

When people think of science fiction, they often picture rockets, Martians, or far-flung futures. Yet the genre’s roots stretch back more than 200 years to a young woman writing by candlelight. In 1818, Mary Shelley published Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus—a novel many consider the first modern work of science fiction. With that one book,

Sources & Further Reading

- Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818 and 1831 editions). The 1818 edition is the original text written by a young Mary Shelley, while the 1831 edition is the heavily revised version she made later in life. Comparing them reveals how her views on the novel’s themes changed.

- Mary Shelley, The Last Man (1826). Her second major speculative work, essential for understanding her role in shaping apocalyptic science fiction.

- Gordon, Charlotte. Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley (2015): This dual biography provides a compelling narrative, situating Mary Shelley’s life and work in the context of her equally famous mother, Mary Wollstonecraft.

- In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg (BBC Radio 4): This is a high-quality radio show that has episodes on Frankenstein and the Romantic poets, featuring leading academics discussing the works in depth.

- Online Frankenstein Resources, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford: A comprehensive curated list of high-quality online resources.

- Mary Shelley’s Journals: Her personal journals offer invaluable insight into her thoughts, experiences, and the events that inspired her writing.

- Mary Shelley (2017), dir. Haifaa al-Mansour — A dramatized biopic focusing on her relationship with Percy Shelley and the creation of Frankenstein.

- Mellor, Anne K. Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters (1988): This is a seminal work of feminist literary criticism that is a standard text in Mary Shelley studies. Mellor focuses on the novel as a critique of patriarchal science and society.

- Seymour, Miranda. Mary Shelley (2000): A highly regarded and comprehensive biography that offers a detailed account of her life.

- The Shelley-Godwin Archive: An excellent digital archive of manuscripts and letters from the Shelley and Godwin family. It’s a goldmine for anyone wanting to look at the original documents.

Frequently Asked Questions

A: Many scholars credit Mary Shelley as the “mother of science fiction” thanks to Frankenstein (1818). While earlier authors dabbled in fantastical voyages, Shelley combined speculative science with human drama in a way that set the foundation for the genre.

A: She was just 18 when she began writing it during the famous 1816 “Year Without a Summer” gathering in Switzerland, and 20 when it was published anonymously in 1818.

A: Yes—most notably The Last Man (1826), an apocalyptic plague novel that many critics see as a forerunner of post-apocalyptic science fiction. She also wrote speculative short fiction, including “The Mortal Immortal” (1833) and “Transformation” (1831).

A: Anonymity was common for controversial works, especially for first-time authors. Coupled with the novel’s shocking subject and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s preface, many assumed he was the author. Gender bias reinforced this misattribution—some still debate it today.

A: The idea came from a late-night ghost-story contest with Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, and others. A dream she had — of a scientist reanimating a corpse — became the seed of the novel.

A: The 1818 text is closer to the youthful, radical conception; the 1831 revision adds a new introduction, reframes some motivations, and leans more toward fate/providence and explicit moral commentary.

Affiliate Disclosure: Some links on this page are affiliate links. If you click through and make a purchase, Founders of Sci-Fi may earn a small commission—at no extra cost to you. Thanks for supporting the site!